The Collemacchia Project

Written while on an artists residency in the Molise region of Italy

Introduction

This piece was written during and after my stay at the Museum of Loss and Renewal residency in the Molise region of Italy. My first few days in Italy were spent in Rome with my family.

Ink is in the way that I wander. I generously apply a layer of water onto a slick barrier. My mind is thick set with fruit when I then apply the ink itself. I observe as I drop in the first black. If the water application precedes it, it spreads and sows seeds on the page. Ink branches out in its shape and saturation. I want the medium to speak, while the transcription between my brain and the brush remains quiet. The ink is a center of mass - an origin story like the big bang theory or turtle island. The water acts as the basic elements of life; carbon, for its endlessly generative and mutable quality.

3 Knots

The irregularity of women is in our shape. It’s in our bodies, disproportionate to the love that God can give us. Yet our bodily poignances cannot totally escape religious imagery. The relationship between poignance and imagery is buried but re-occuring much like the governing lunar cycle. And although these waning and waxings are omnipresent among women, they are often ignored in a medical and historical sense. While in the Vatican, paintings such as The Fire in Borgo struck me with seduction. The rendered looks of ecstasy, the meaty bodies of women, men and children that strike acrobatic poses in a frozen frame. The painting erotices each figure; even the children. The Side Wound of Christ, an example I have long since looked at, is a vaginal void or a sacred window but is often perceived as something else.

While I was a tourist in Rome, I couldn’t help but make certain connections. I started off at the Museo e Cripta dei Capuccini, a museum that holds the bodies of 3,700 friars. Their bones are made into arches, tombs, a winged hourglass, because time doesn’t just move - it flies (fig 1). The museum displays the friar’s hood and the three time knotted rope behind a display case. What is profane in nature is veiled in flesh. The hood in both feminine and masculine terms protects something deeply sensitive and fleshy. The friar earns his knots based on three vows; poverty, obedience, and chastity. The knots of womanhood are triadically inverted; symbolising sexual disease, beating, and imperfection. As eroticism is no secret among the church and its visual canon, it is also a symbolic mirroring of women. Though this idea would lend itself to a clitoridectomized world, it can also be said that divine femininity exists in the otherwise phallicized monkhood – even if abused.

Figure 1: Winged Hourglass, made of bones, Museo e Cripta dei Capuccini, shot on iPhone

The Apple and the Torso

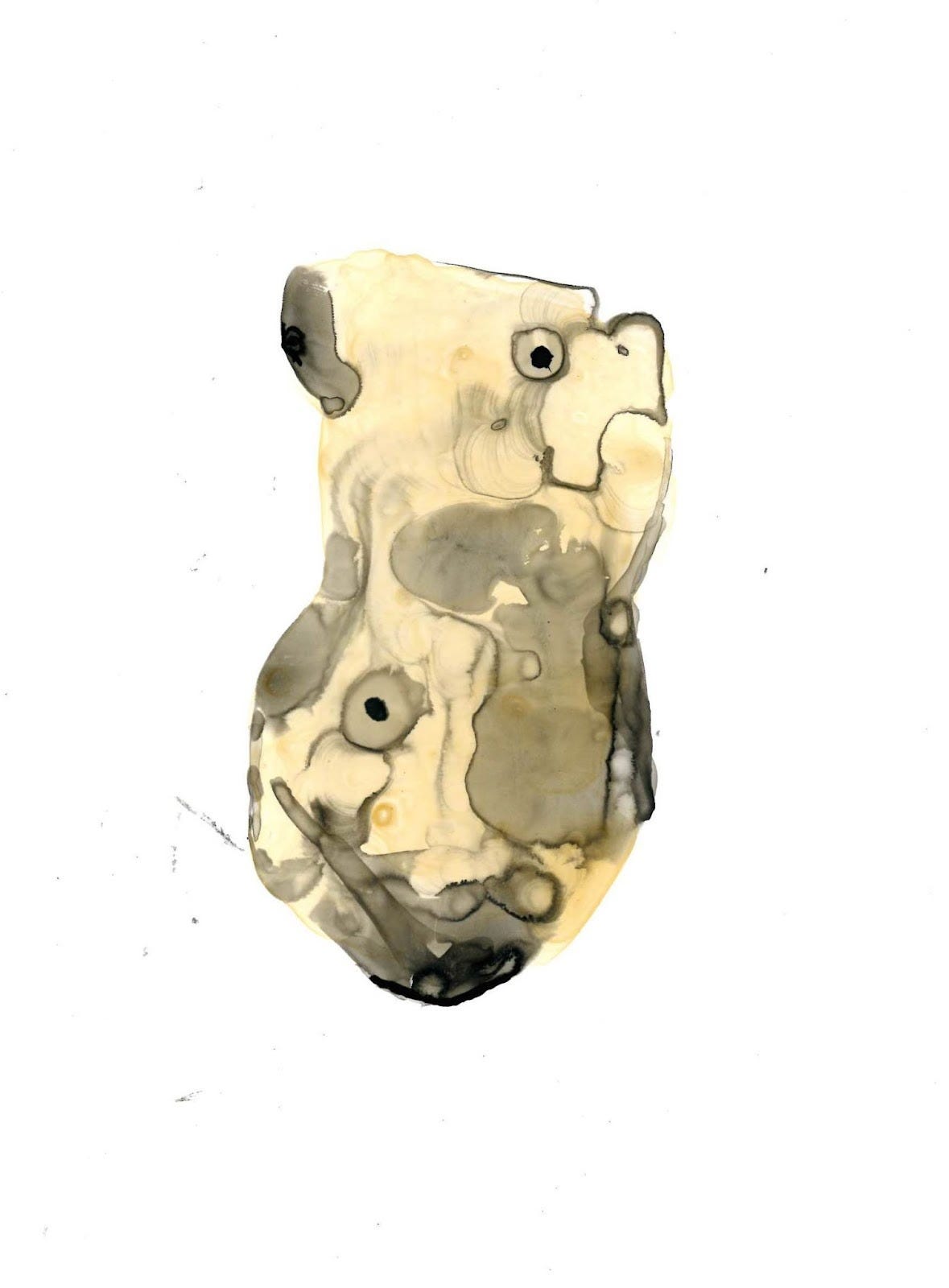

In my first round of ink drawings, I mainly referenced halved apples and torsos. I painted apples by only applying ink to the outer rim and the seeds in the middle, letting the ink bleed slightly past its own boundaries. Once the ink is dry, I add a wash of home-made amber over the apple, making the color world feel sepia-toned and archaic (fig 2 and 3). Ironically, the ink I made is of oak gall collected in the woods - in some places otherwise known as ‘oak apple’. The apple is a reference to my earlier works. I was intuitively drawn to its roundness and symmetry, suggestive of a gravitational pull. Even more compelling to me was the flesh of the apple—its soft, white belly—and the seeds, embryonically arranged at its center, evoking the anchor of an atom or a galaxy. I think of the apple as the “first decision”, as it’s often called the “first sin” through a biblical and metaphorical disposition.

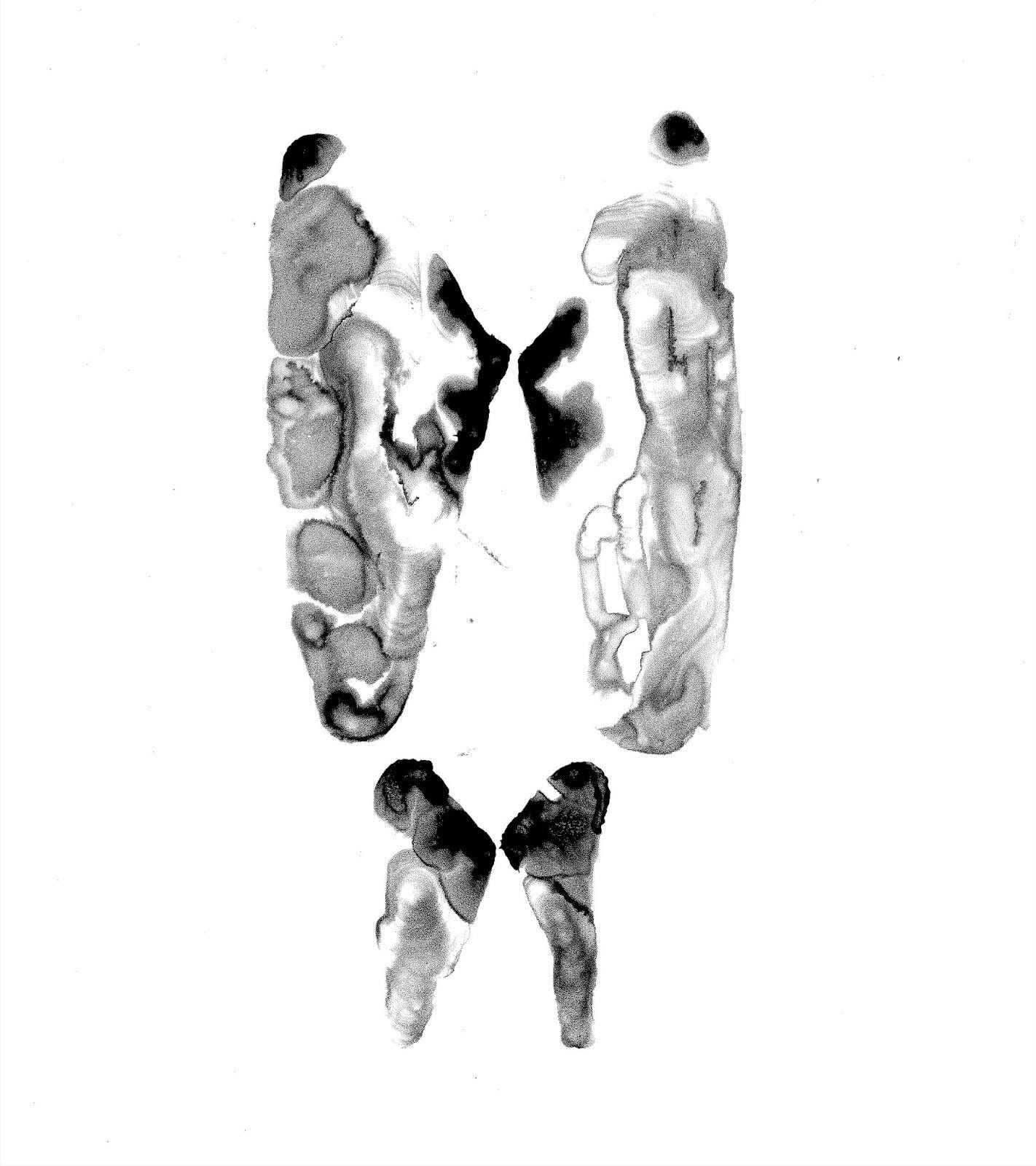

A layer of water, in the shape of a figure, is applied to a slick piece of yupo paper; a water-proof and synthetic paper. Controlled amounts of ink are brought down upon the water and a shadow structure is loosely implemented. The genitalia, the nipples, and bellybuttons are treated with straight ink. The ink spreads like a pool of blood, in this way areolas and surreal irregularities are created. The reference for the torsos are from memories from what I viewed at the Vatican and a small museum in Venafro. I envisioned the swollen belly of Eve, or the fleshy midsection of a cherub. In these moments of flesh, I relate that in that I feel the swelling of my own stomach.

Figure 2: Apple I, 2025, india ink and oak apple on paper

Figure 3: Torso I, 2025, india ink and oak apple on paper

Hole in the Landscape / Clash

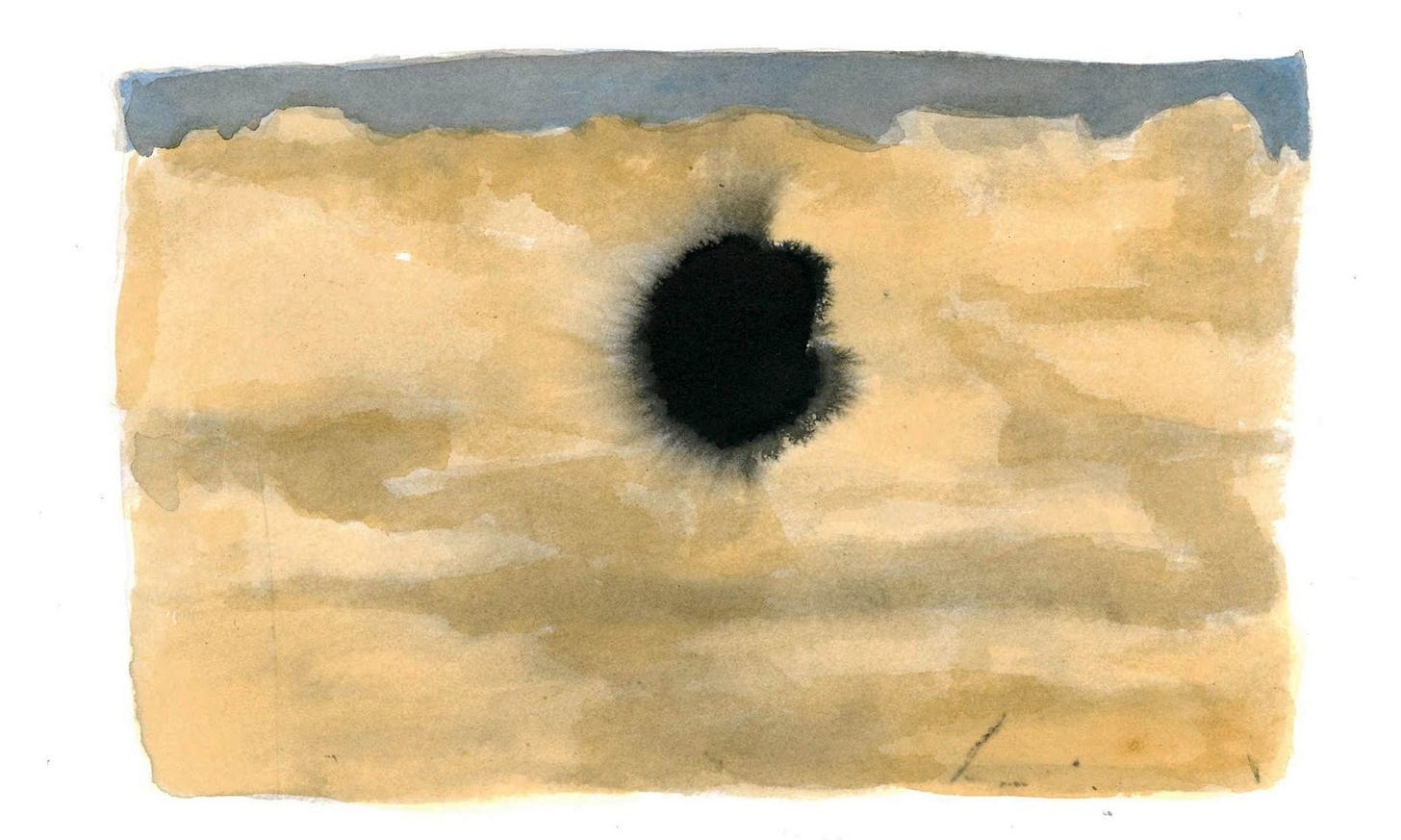

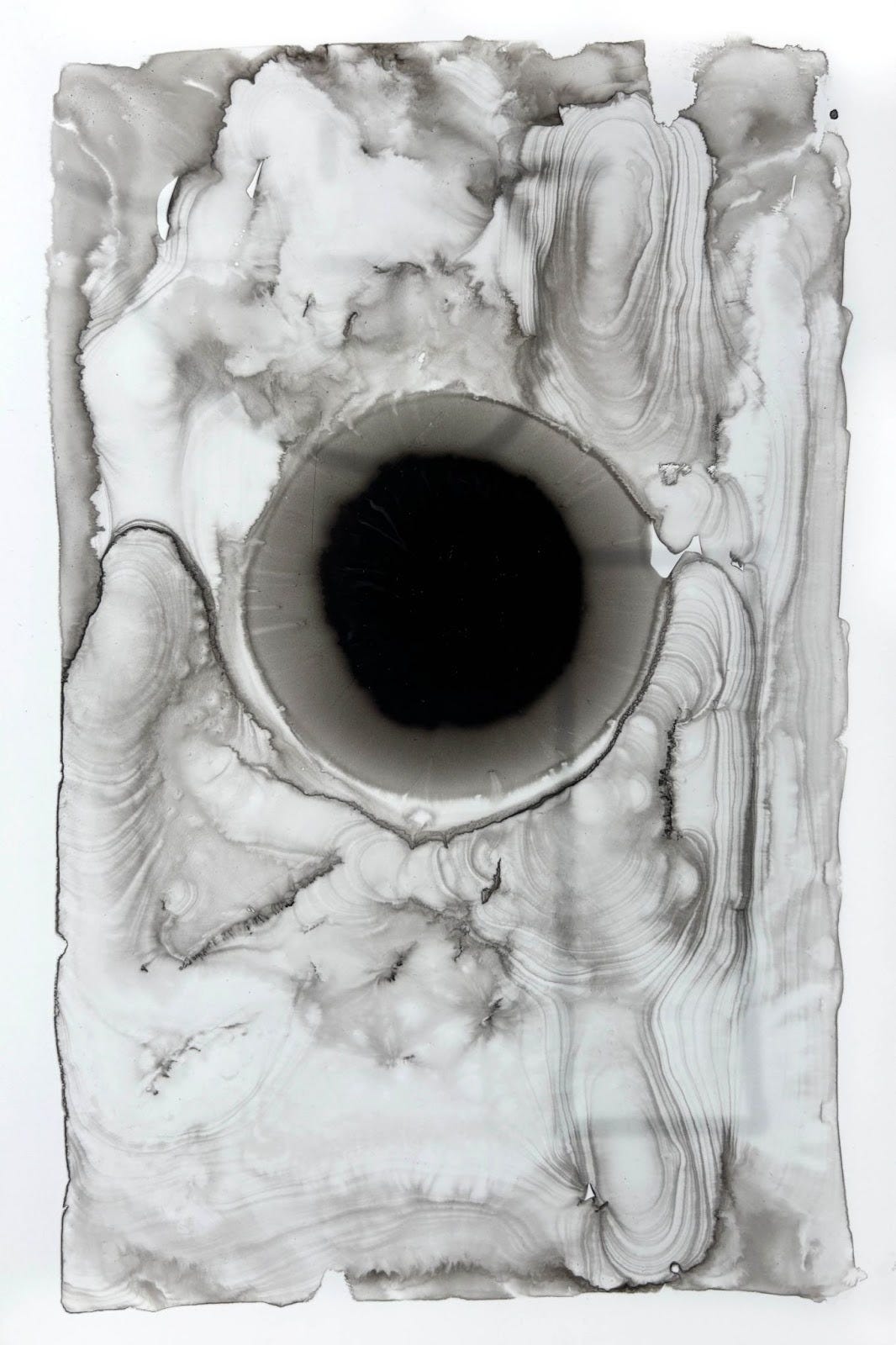

In Scotoma I (Figure 4), a scotoma like orb lands onto the painting and precedes all ground. The spot impedes on visibility. It is both a dense center of gravity and a pit for memory to fall into. In some pieces the landscape is realized and lacks the orb altogether, while in others the landscape is only as present as abstracted clouds. The material differences in paper dictate whether the orb will seep into the ground or hovers above the ground like in Scotoma II (Figure 5), which aesthetically resembles how the subconscious is both controlling yet nebulous. There are moments where the world feels like it’s condensed into opacity. Borne out of winds we fold into ourselves; a collapsed origin often suspended at our own climax.

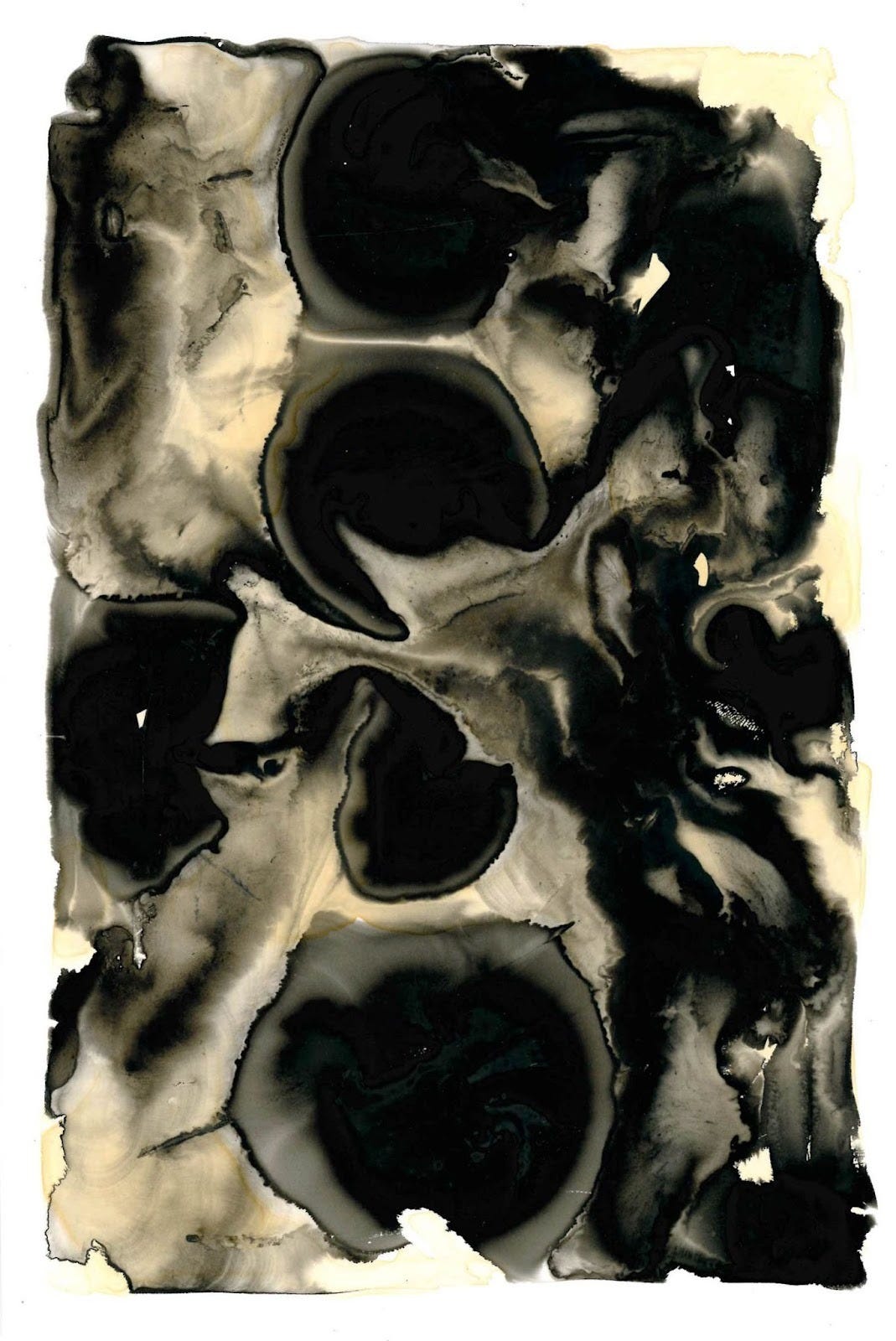

In some pieces where I used an ink dropper into water, cellular material pushes against each other. The blackness of the ink seems to envelop most of the page, giving almost the technological appeal of an ultrasound, as seen in Clash I (Figure 6). I press my fingers neutrally and sporadically on the paper. The oil from my fingertips counteracts both ink and water, suspending the whiteness of the paper. Like a running current, the amber wash of the oak apple is laid over some of the ink dropper pieces (Figure 7) and some are left black and white. The play of touch and resistance as a presence reflects itself unto the visual themes at large, and thinking back to monkhood where the flesh becomes a vow, the “resistance” is set in reality, while the “touch”, where the ink meets the page, there is an unpredictable bleeding set in fantasy and falsehood.

Figure 4: Scotoma I, 2025, india ink and oak apple on paper

Figure 5: Scotoma II, 2025, india ink and oak apple on paper

Figure 6: Clash I, 2025, india ink and oak apple on paper

Figure 7: Clash II, 2025, india ink and oak apple on paper

To Have and To Hold

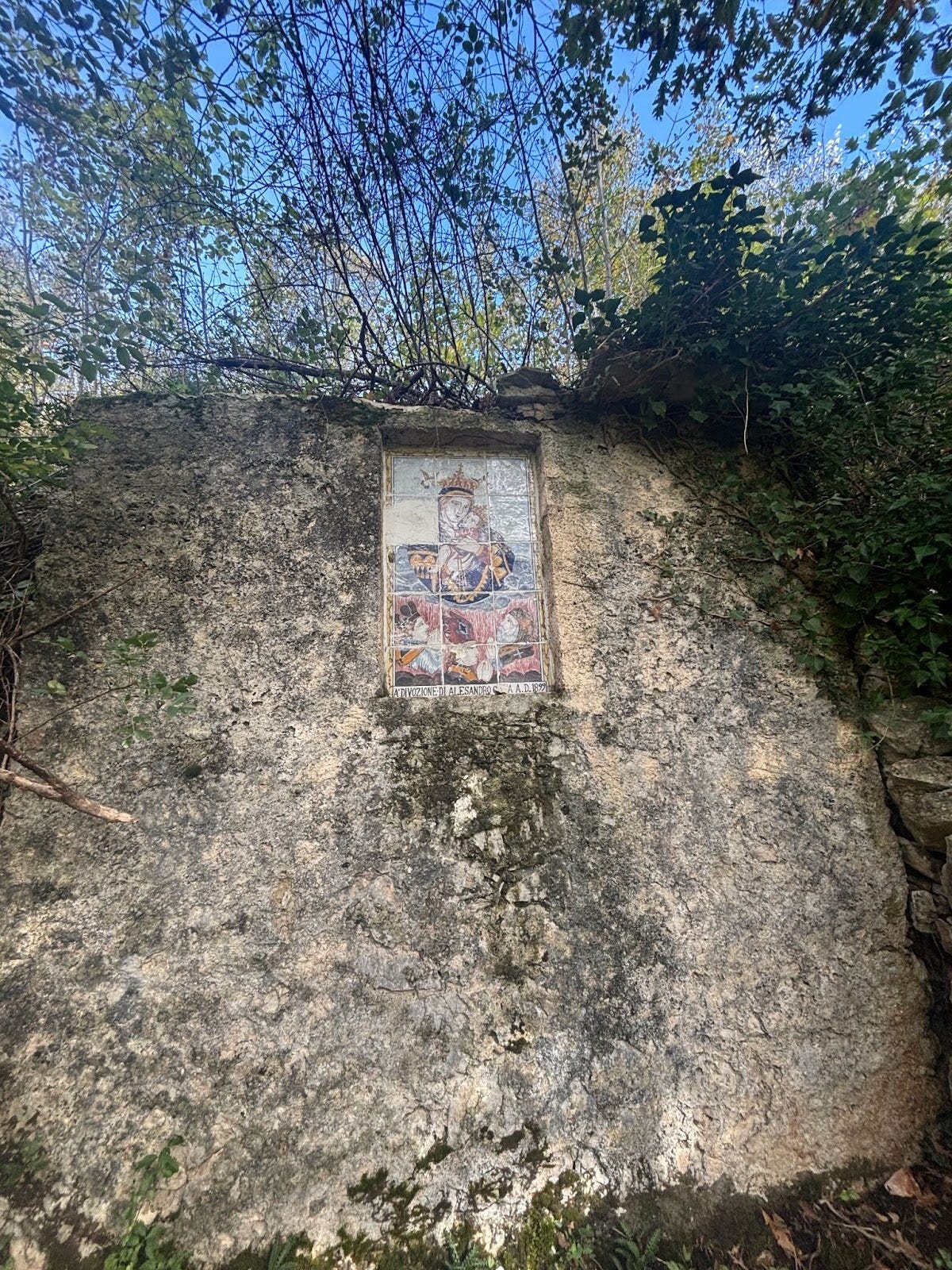

Memento, by definition, is a souvenir or a keepsake. When I frequent the tidal pools at home, shells and small animal bones stay in my hand. I feel their calcium carbonate markings in my palm, which is slightly eroded and weathered by the harsh salt and wind of the Maine coast. During the residency I held onto found porcupine quills and of course the oak galls. Catholic shrine tiles existed throughout the woods and the small town of Filigano (Figure 8), which inspired Tile Study (Figure 9). These open-air spaces of worship, also called edicole votive, held me in a meditative and quiet space. I began to imagine a type of underlying vibration behind each tile, embedded in the grout. To gaze at and to cradle are both ways of being inside of.

Like previously mentioned, I began to think about the murals and what lays behind them. For this reason, I used black paper and white pencil in Tile Study. This way, I was building light rather than adding shadow. I studied the faces of Mary and Jesus: their indifferent expressions, specifically the space between the brow and the eye, the plumpness of their cheeks, and the simplicity of their lips.

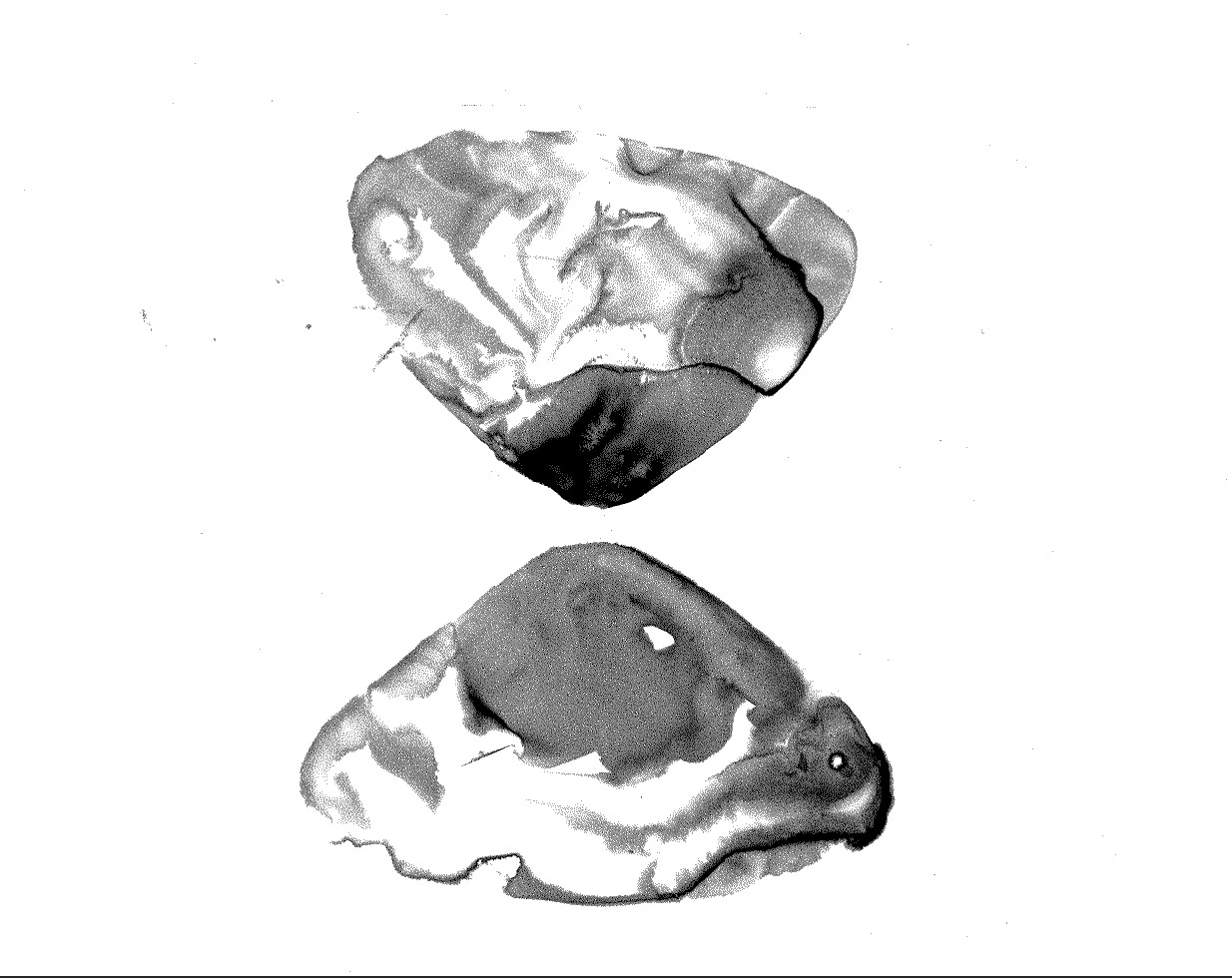

While both A Quiet Split I and II (Figures 10 and 11) follow suit of many of the other pieces, there is an important notion of distance that differentiate them from the rest. Imagined studies of miscellaneous bones and clam shells, consequential to my missing home, became a part of the body of work. Though the distance between my home and I was pushed to the back of my mind, it was the little hand-held objects that made themselves known in the work. There is a doubling effect within these studies, which I now like to think of as double-vision, or diplopia. Once again, references to vision as a vehicle for the subconscious is present, however there is a very tangible language that puts both the metaphor and the optical into motion.

Figure 8: ‘Edicole votive’ of Mary and Jesus in the woods behind the village of Collemacchia, shot on iPhone

Figure 9: Tile study, 2025, india ink and white colored pencil on paper

Figure 10: A Quiet Split I, 2025, india ink on paper

Figure 11: A Quiet Split II, 2025, india ink on paper

References

Bennett, Paula. “Critical Clitoridectomy: Female Sexual Imagery and Feminist Psychoanalytic Theory.” Signs, vol. 18, no. 2, 1993, pp. 235-259. JSTOR.

Cleghorn, Elinor. Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World. Penguin Publishing Group, 2021. Accessed 11 October 2025.

Hampton, Rosalind, and Ashley DeMartini. “We Cannot Call Back Colonial Stories: Storytelling and Critical Land Literacy.” Canadian Journal of Education, vol. 40, no. 3, 2017, pp. 245-271. JSTOR.

Manlove, Clifford T., and Laura Mulvey. “Visual “Drive” and Cinematic Narrative: Reading Gaze Theory in Lacan, Hitchcock, and Mulvey.” Cinema Journal, vol. 46, no. 3, 2007, pp. 83-108. JSTOR.